Edward Avery McIlhenny and the Ivory-billed Woodpecker in the Coastal Forest of Louisiana

David L. Martin

Note: This publication has not been peer-reviewed.

For those familiar with the bird, James T. Tanner is almost synonymous with the Ivory-billed Woodpecker. His study of the species in the Singer Tract in Madison Parish, Louisiana (Tanner, 1942), with rather sweeping conclusions about the species’ biology, is relied upon by many in the ornithological community. Yet Tanner himself cautioned that “The chief difficulty of the study has been that of drawing conclusions from relatively few observations, necessary because of the extreme scarcity of the bird. My own observations of the birds have been entirely confined to a few individuals in one part of Louisiana, and although these observations covered a large percentage of all the Ivory-bills living in the country, the conclusions drawn from them will not necessarily apply to the species as it once was nor to individuals living in other areas.” In fact Tanner studied only one pair of Ivory-bills closely, and his assumption that the Singer Tract birds constituted a large percentage of the species population at the time is highly questionable. Tanner never saw an Ivory-bill outside the Singer Tract himself, and relied upon cursory examinations, interviews with locals, and particularly, assumptions about carrying capacities, to estimate population densities.

Time and again in his travels, Tanner was told by locals that they no longer saw Ivory-bills, or saw them rarely, often after industrial logging had swept the area. Time and again he pointed to “virgin” forests as necessary to provide critical forage. He estimated the entire species population in 1939 at only about 22 birds. Five of the 6 areas in which he felt the birds persisted contained significant tracts of uncut forest at the time, with the Singer Tract supposedly housing 100% of the Louisiana population. Yet we now know that a significant portion of the area favored by the birds in the Singer Tract was in fact second-growth forest. We also know that the Cuban Ivory-bill, with a much smaller geographic range than the North American bird, survived for decades among cut-over pinelands. The Imperial Woodpecker of Mexico is also believed to have persisted at least 40 years after the last clear documentation of the species in 1956 (Lammertink et al., 1997), and even Tanner believed that it suffered decline due mainly to human predation (Tanner, 1964).

The Singer Tract overwhelmingly consisted of bottomland hardwood forest, some of it relatively high, almost 200 miles from the coast. Yet across the range, most Ivory-bill specimens came from within 40 mi of the coast, where cypress becomes more prevalent and hurricane impacts become more prominent. Almost half of all of the Ivory-bill nests for which the nest tree species was reported in the literature (12 out of 25) were found in cypresses. The vast majority of nests from Florida, where the species seems to have been most abundant, were recorded in cypress trees.

One other naturalist is known to have observed Ivory-billed Woodpeckers in a particular area over many years – Edward Avery McIlhenny. He was born in 1872 at Avery Island, in coastal Iberia Parish, Louisiana, when much of the landscape in that area was a virtual wilderness, and flocks of Attwater’s Prairie chickens, Whooping Cranes, and Carolina Parakeets were common sights. McIlhenny published a number of works on the wildlife of South Louisiana, including a classic treatise on the American Alligator, in which he debunked a number of published falsehoods concerning the species. He corresponded extensively with biologists and wildlife agencies on a wide variety of species.

In 1943 McIlhenny published a paper describing the changes in bird life he had witnessed in South Louisiana over the previous 60 years. In this paper, McIlhenny described in some detail the increases and declines over the previous decades of species as diverse as the Pectoral Sandpiper and Loggerhead Shrike. This publication also contains one of four published accounts originating from him concerning the Ivory-billed Woodpecker. His correspondence contains other information about the bird and the area. Avery Island is one of the “Five Islands,” salt domes with significant surface expression in Iberia and St. Mary Parishes. The highest point on Avery Island is 163 ft above sea level. Weeks Island, about 8 mi to the southeast, is even higher, 171 ft at its highest point. These are the highest points in South Louisiana.

Avery and Weeks Island were undoubtedly covered with upland hardwood forests in presettlement times, and contain remnant tracts to this day. However, significant areas of forest on both were cleared for agriculture even in the 19th century, initially for sugar cane and later for sugar cane and tabasco peppers. Lockett (1871), quoting Dennett, described Avery Island as about 55% forest, the forest covering 1200 arpents, or about 1.6 mi2. This provides a reasonable estimate of the extent of upland hardwood forest on the Island in McIlhenny’s time.

McIlhenny (1943) described the area surrounding Avery Island when he was growing up as “low, wet prairies or marshes near the coast, and higher, dry prairies farther inland. The only forests in this whole area were lines or groups of trees bordering the streams making inland from the Gulf.” However, in his 1941 paper on the Ivory-bill he mentioned the “great forest” extending eastward from Avery Island to the Atchafalaya River. McIlhenny was mainly concerned with the “twelve square miles” of forest just east of the Island – the Avery Swamp, where he collected Ivory-bill eggs and adults in the 1890’s.

Years prior to McIlhenny’s birth, in the mid 19th century, surveyors of the General Land Office characterized the landscape in this region. Witness trees were usually recorded at section corners. Transitions from one vegetation type to another along the section lines were also noted. Avery Island straddles the boundary between two townships: Township 13 South, Range 5 East and Township 13 South, Range 6 East. These townships were surveyed between 1820 and 1860 by surveyors John Boyd, A.L. Fields, and William Johnson.1

Based on descriptions of these surveyors, the landscape at Avery Island and the surrounding area during the mid 19th century can be divided into 9 vegetation types, as follows:

prairie

open marsh

upland hardwood forest (on Avery Island) – “magnolia and gum wood land,” “high cane land”

bottomland hardwood forest – “high wood land,” “high land,” “high wood land vines and briars,” “wood land”

maple swamp – “maple swamp, briars and vines,” “scrubby maple swamp”

willow swamp – “willow marsh,” “willow growth,” “myrtle and willows”

cypress/tupelo swamp – “myrtle and tupelo,” “low swamp,” “tupelo swamp,” “cypress swamp,” “swamp,” “cypress and tupelo”

wax myrtle/bay/live oak scrub – “scrub myrtle bay,” “scrubby myrtle bushes,” “scrub growth and high palmetto,” “myrtle and scrub live oak,” “scrubby swamp,” “myrtle bay and live oak,” “myrtle and bay,” “myrtle and bay thicket,” “myrtle swamp,” “myrtle thicket”

scattered cypress (transition between cypress/tupelo swamp and wax myrtle/bay/live oak scrub or open marsh) – “scattering cypress,” “scrubby cypress and myrtle”

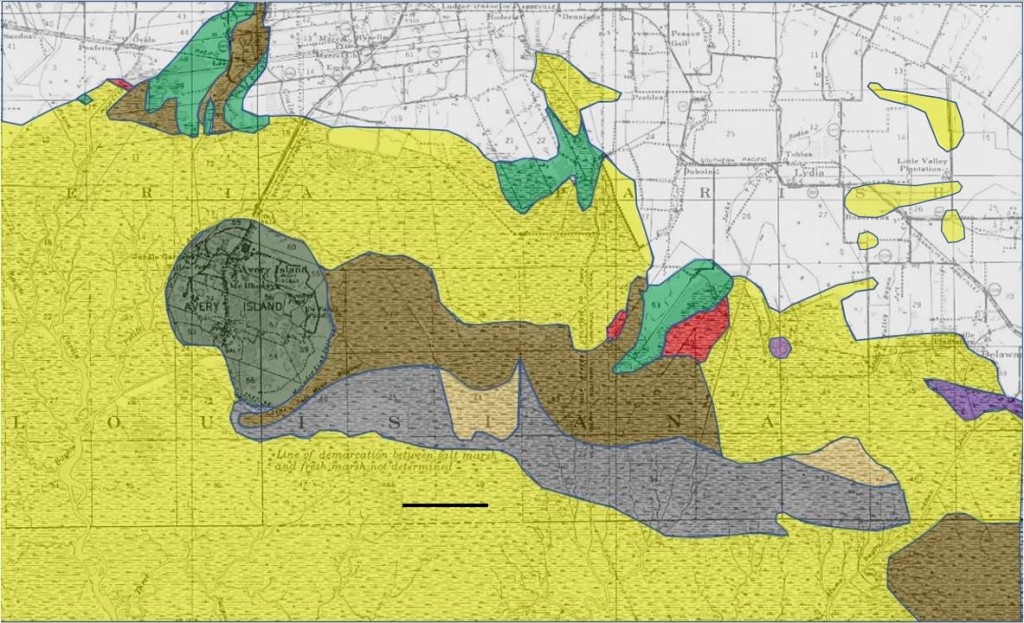

Using the surveyors’ notes as a guide, I have mapped each vegetation type (Fig. 1). Agricultural fields did occur on the prairie and Avery Island itself in the mid 19th century. Most of the prairie was under the plow by 1900. This is ignored for the purpose of mapping; however, the figure of 1.6 mi2 noted above will be used as an estimate of the extent of upland hardwood forest.

Fig. 1. 19th century vegetation map of the Avery Island area, based on surveys of the General Land Office, 1820-1860. Dark brown – cypress/tupelo swamp; light brown – scattered cypress; dark green – upland hardwood forest; light green – bottomland hardwood forest; purple – maple swamp; red – willow swamp; gray – wax myrtle/bay/live oak scrub; yellow – open marsh; white – prairie. Avery Island and the prairie region contained agricultural fields which are not mapped. The black line is 1 mi in length.

As can be seen, much of the area consisted of prairie and open marsh, in agreement with McIlhenny’s description. Witness tree information within each of the 7 forest and scrub types is shown in Table 1. Survey corners falling along the banks of Bayou Petite Anse, north of Avery Island, are excluded.

| witness tree type | UHF | BHF | MS | WS | CTS | SC | SCRUB |

| cypress | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 0 |

| tupelo | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 11 | 0 | 0 |

| maple | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| live oak | 2 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| sweet gum | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| red oak | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| water oak | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| white oak | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| unidentified oak | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| magnolia | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| black walnut | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| wild peach | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| hackberry | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| elm | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| hickory | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| mulberry | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| “gum” | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| willow | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| bay | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 9 | 4 | 12 |

| myrtle | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 8 |

| “cassine bush” | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

Table 1. Witness trees by vegetation type (excluding prairie and open marsh) in Township 13 South, Ranges 5 and 6 East. Vegetation types: UHF – upland hardwood forest (on Avery Island); BHF – bottomland hardwood forest; MS – maple swamp; WS – willow swamp; CTS – cypress/tupelo swamp; SC – scattered cypress; SCRUB – wax myrtle/bay/live oak scrub. Surveyed 1820-1860 by John Boyd, A.L. Fields, and William Johnson.

Many survey corners fell upon the banks of Bayou Petite Anse north of Avery Island. A total of 51 witness trees were recorded at these, as follows:

tupelo 29

cypress 10

hackberry 2

sweet gum 2

ash 2

hickory 2

sweet bay 1

maple 1

persimmon 1

honey locust 1

Since tupelo and cypress were the dominant trees recorded along Bayou Petite Anse, this may be considered a variant of cypress/tupelo swamp, and I have mapped it as such in Fig. 1. Most of these witness trees were recorded by John Boyd, who surveyed this area between 1844 and 1848. He also recorded the diameters of many of these trees. The diameter distributions are shown in Fig. 2. This gives some idea of the size distributions of these species in uncut cypress/tupelo swamps in the area. Of 40 witness trees, only 4 had recorded diameters greater than 25 inches. Two of them were cypresses. Unfortunately, witness tree diameters were not generally recorded in the Avery Swamp itself.

Fig. 2. Diameter distributions of witness trees along banks of Bayou Petite Anse, Township 13 South, Ranges 5 and 6 East. Surveyed by John Boyd, 1844-1848.

From Fig. 1 above, and the Avery Island forest area reported by Lockett (1871), I estimate the coverage of each of the forest and scrub types in the area as follows:

upland hardwood forest (Avery Island) – 1.6 mi2

bottomland hardwood forest – 2.34 mi2

maple swamp – 0.38 mi2

willow swamp – 0.50 mi2

cypress/tupelo swamp – 5.65 mi2

scattered cypress – 1.11 mi2

total forest – 11.58 mi2

wax myrtle/bay/live oak scrub – 4.96 mi2

If we include willow swamp, scattered cypress, and scrub, the area of the Avery Swamp was 11.2 mi2.

Note that I have excluded from these estimates the tract of cypress/tupelo swamp in the southeastern corner of Fig. 1. However, the coastal forest continues east of the Avery Swamp. A large area of cypress/tupelo swamp lies in Township 14 South, Range 7 East, just east of Weeks Island. This township was surveyed by A.L. Fields in 1848. A vegetation map constructed from his field notes in shown in Fig. 3.

Fig. 3. 1848 vegetation map constructed from surveyor’s notes, showing sizable area of cypress/tupelo swamp in Township 14 South, Range 7 East. The center of the swamp is about 12 miles southeast of Avery Island. Surveyor: A.L. Fields. Dark brown – cypress/tupelo swamp; dark green – upland hardwood forest; light green – bottomland hardwood forest; purple – maple swamp; gray – wax myrtle/bay/live oak scrub; yellow – open marsh; white – prairie; blue – open water. Agricultural fields covered sizable portions of Weeks Island as well as the bottomland hardwood forest area in the lower part of the figure in McIlhenny’s time; these are not mapped. The black line is 1 mi in length.

The numbers of witness trees recorded by Fields in the cypress/tupelo swamp were as follows:

tupelo 50

cypress 30

maple 4

ash 2

bay 2

Again we see an abundance of tupelo long before the forest was logged. Although Fields only recorded the diameters of 17 of the witness trees in this swamp, the distributions are instructive (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4. Diameter distributions of witness tress in the cypress/tupelo swamp within Township 14 South, Range 7 East. Surveyed by A.L. Fields in 1848.

Here again we see a clear indication that most of the larger trees were cypresses. Like the Avery Swamp, this swamp was flanked by a sizable area of scrub along with open marsh.

It seems clear that tupelo (Nyssa spp.) was abundant in the cypress/tupelo swamps of the area many decades before these swamps were cut over. However, most of the larger trees were likely cypresses, as remains true in much of the coastal forest today, even in many areas of second-growth. Even within the cypress swamps of the Atchafalaya Basin, tupelos have always been common. In surveys across 4 townships deep in the southern Basin by H.T. Williams and J.C. Naylor in the 1830’s2, tupelos outnumber cypresses among the witness trees by a ratio of 1.6:1. However, 72% of the witness trees 35+ inches in diameter were cypresses, and in basal area, the ratio of tupelo to cypress is 0.74:1.

As can be seen above, areas identified as scrub contained overwhelmingly bay, myrtle, and live oak. To this day, extensive areas of scrub live oak (Quercus virginiana), wax myrtle (Myrica cerifera), and bay (Persea spp.) can be found just north of the marsh between Weeks Island and Lydia (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5. Tract of scrub live oak, wax myrtle, and bay between Weeks Island and Lydia, in the eastern portion of the Avery Swamp. Avery Island is visible in the distance.

A soil survey published in 1911, 7 years before the Avery Swamp was logged, more or less comports with vegetation patterns revealed by the 19th century surveys (Fig. 6). The Avery Swamp is simply characterized as “swamp.” The land surrounding Avery Island and Avery Swamp is characterized as “tidal marsh.”

Fig. 6. Soil type map of the Avery Island area published in 1911 (Mann and Kolbe, 1911). The pale yellow area was characterized simply as “swamp.” The light green area is labeled “tidal marsh.”

The 11-12 mi2 Avery Swamp, just east of Avery Island, was only the small westernmost extremity of a much larger area of coastal forest and scrubland, referred to as the “great forest” by McIlhenny (1941), extending to the Atchafalaya River (Fig. 7). The bulk of this forest, primarily in St. Mary Parish, contains sizable tracts of hardwood-dominated forest with cypress overstories. The hardwoods are generally less than 70 ft in height, and many show signs of having been broken off by hurricanes. The coastal forest and associated scrub cover about 150 mi2. However, in McIlhenny’s statements regarding his direct observations of Ivory-bills, he consistently mentions Avery Island itself and the forests just to its east.

Fig. 7. Mosaic of USGS quadrangles showing the coastal forest of South Central Louisiana in the 1930’s and 1940’s. Forested areas and scrublands are shown in green. The Derouen quadrangle, which encompasses Avery Island and the Avery Swamp, was published in 1937, the same year that Tanner visited McIlhenny. The black line is 5 mi in length. Source: USGS Historical Topographic Map Explorer.

In his 1941 paper on the Ivory-bill, McIlhenny noted that even the “French-speaking natives” were well aware of the difference between the Ivory-billed and Pileated Woodpeckers, referring to the former as the “Pique-bois grande” and the latter as the “Pique-bois noir.” Although McIlhenny was known to be a “spinner of tall tales,” there is a world of difference between personal tales and careful observations. Ouchley (2013) challenged McIlhenny’s claim that he measured an alligator to be 19 feet 2 inches long in 1890, noting that among many thousands of alligators in existence today, the record length appears to be about 15 feet. This overlooks the fact that McIlhenny himself noted the tendency for hunters to exaggerate alligator sizes, and provided detailed information on 4 other alligators that exceeded 17 feet in length. He even provided a photograph of a skin, alongside a scale, that after tanning measured 17 feet 9 inches. Ouchley himself stated that McIlhenny’s book “is obviously based on long-term observations, experiments, measurements, and extensive notes.”

McIlhenny (1941), in a paper lamenting the decline of the Ivory-bill, mentioned the “twelve square miles” of forest just east of the Island. In a letter to Tanner in 19373, he stated that “The territory covered by these birds is about 10 square miles….” (Fig. 8). In other correspondence, McIlhenny described the swamp east of the Island in more detail. In a letter to J.M. Avent in 1917, he stated, “The country is not big, only about two miles wide and eight miles long….” In a second letter to Avent 4 days later, he stated, “Last winter I found where the bear den, and it is in a thicket about a mile and one-half wide by three miles long, between two bayous….This is right in the center of the swamp….I am going out this morning to cut a trail directly through the center of the swamp where we hunted, running through the big timber from the Island to the Commercial Canal, a distance of about four miles.” In a 1920 letter to L.N. Kimerer, he wrote, “Paul Rainey will be here with his dogs and am going to make the camp at the second canal….” These letters to Avent and Kimerer4 are invitations to bear hunts. The 1920 hunt is described in articles in The Wide World Magazine (Dunn, 1921) and Motor Boat (Morgan, 1921), which provide considerable detail about the swamp and its relationship to the canals and bayous in the area, including descriptions of the dense thickets of palmetto, wax myrtle, and live oak.

Fig. 8. Response to James Tanner from McIlhenny, 27 Mar 1937.

In his book on the American Alligator, McIlhenny (1935) described in detail the work on a den by a large alligator “about two and a half miles back in the heavy cypress swamp east of Avery Island.” He stated that he had known of this alligator in this particular den for more than 30 years. To this day, the lands of Avery Island, Inc., and E.A. McIlhenny Enterprises to the east of the Island are confined to within 8 miles of Avery Island itself. In none of his correspondence or publications does McIlhenny suggest that he spent a significant amount of time in the coastal forests farther east. Although he clearly had contacts among other observers in the coastal region and elsewhere, the evidence strongly indicates that McIlhenny’s direct observations of Ivory-bills in the swamp east of Avery Island were confined to within 8 miles of the Island.

Beginning around 1900, logging proceeded generally from east to west in the coastal forest of Louisiana. McIlhenny (1941) noted that “the shyer birds and mammals kept ahead of the cutters, moving west in the primeval forests.” He remarked that by 1918, black bears and Ivory-bills were unusually abundant at Avery Island and in the forests just to its east. Industrial logging reached the Avery Swamp that year. The destruction of the forest and the noise of the operation drove the bears and Ivory-bills away from the area. Apparently, the bears did not stay away for long. Judging by the accounts of the bear hunt in 1920, the Avery Swamp contained large numbers of bears a few years after the logging. “More than thirty separate trails were reported by the hunters, all of bears which the hounds were not chasing….” (Dunn, 1921). At least 1 pair of Ivory-bills also nested in the swamp in 1920 and 1921.

It should be noted that the logging canals only reached about 1.2 mi into the Avery Swamp from the west. Pullboat traces radiating from the canals are still clearly visible in 1940 aerial photos (Fig. 9) but do not extend to the eastern part of the Avery Swamp. Presumably this area was passed over by the loggers because the cypresses were too stunted, too scattered, or both, for industrial logging to be cost-effective in this area.

Fig. 9. 1940 aerial photo showing a small part of the Avery Swamp 1-2 mi east of Avery Island. Note the logging traces radiating from the pullboat canal near the upper edge of the image.

The eastern portion of the Avery Swamp (where the 1920 bear hunt occurred) contained mostly scattered cypress and scrub. To this day, open forests containing stunted, flat-topped cypresses can be found in this area, with no evidence of logging (Fig. 10).

Fig. 10. Open cypress forest with stunted trees in the eastern portion of the Avery Swamp, between Lydia and Weeks Island. This area was characterized as “scattering cypress” by 19th century land surveyors. There is no evidence of industrial logging in this area.

Other tracts of coastal forest show similar patterns. In areas subjected to industrial logging, the evidence of same is clearly visible in early 20th century aerial photos. Present-day ground reconnaissance usually reveals cypress stump remnants in such areas. In other nearby areas, where there is no evidence of cutting, no stump remnants are visible, and flat-topped cypresses are usually present. Almost invariably, these are areas where the cypresses are either stunted, or scattered, or both (Fig. 11).

Fig. 11. 1940 aerial photo showing forest just west of Wax Lake Outlet in St. Mary Parish. Note the clear evidence of timber cutting near the railroad. Ground reconnaissance reveals remnant cypress stumps in this area to this day. Just to the south and southwest, there is no evidence of timber cutting; this area has scattered large cypresses and no remnant stumps. Image source: Cartographic Information Center, Louisiana State University.

In correspondence with Bendire on the Ivory-bill (Bendire, 1895) McIlhenny had stated that “I have observed several pairs of them year in and year out.” In 9 Apr 1892, he collected 3 eggs from an Ivory-bill nest in the swamp near Avery Island (identified as “Avery Swamp” in Bent, 1939), and on 19 May of the same year collected another 4 eggs from a nest excavated by the same pair in the same tree. 17 days prior to collecting the second set of eggs, he reported finding a third set of 3 eggs. Since it is almost certain that this third set was from a different pair than the other 2, this indicates a minimum of 2 nesting pairs in the area. In a letter to Bendire in March of 18945, McIlhenny stated that he had observed 4 Ivory-bills in “the swamp” that Jan (Fig. 12). In an interview with Bendire later that year, he reported that he found a nest in early May in a “gray oak” with 5 young “about 3 days old” (Bendire, 1895). Years later, in 1935, he commented to Arthur Allen that there had once been four or five Ivory-bill pairs living in his swamp (Bales, 2010), and sent Allen a pair of Ivory-bill specimens. These specimens reside in the Cornell University Museum of Vertebrates and were collected on 7 Apr 1895. In his 1941 paper, McIlhenny stated that “three to seven pairs” of Ivory-bills had nested yearly in the area.

Fig. 12. Excerpt of letter from McIlhenny to Charles Bendire, 18 Mar 1894.

McIlhenny was one of the few people to observe and report on Ivory-bills over a period of decades. His writings about the species sometimes deviate markedly from those of others, but he is hardly unique in this regard. Haney (2021) noted that “Our reading room for the ivory-billed woodpecker is full of blatant contradictions.” Allen and Kellogg (1937) reported that Ivory-bills never vocalized in flight. McIlhenny (in Bendire, 1895) stated the opposite: “The only note I have heard these birds give is made while on the wing….They are very silent birds at all times, and during the breeding season I have never heard their cry.” Tanner on the other hand reported Ivory-bills calling while perched and in flight. In response to Arthur Allen’s desire to get sound recordings of Ivory-bills, McIlhenny stated6, “Ivory-billed Woodpeckers begin nesting in March, but until the young birds are hatched, the old birds are very silent. The best time to get records of them would be about the middle of April. The young are clamoring for food, and the old birds are very active.” Unlike Tanner and others, McIlhenny never reported Ivory-bill nesting activity before March.

McIlhenny (in Bendire, 1895) stated that, regarding Ivory-bills, “The nest is generally placed in a cypress or tupelo gum tree, one that is partly dead being preferred, and the cavity is excavated in the dead part of the tree.” He reported that one Ivory-bill nest, described as “typical,” was “in a partly dead cypress, 41 feet up.” After he removed one set of eggs from a nest in Apr of 1892, the same pair nested again in the same tree, the second cavity “in a lower excavation.” Unfortunately he did not identify the tree species in this case. In 1920 and 1921, he observed successive Ivory-bill nests in the same “large deadened cypress” (McIlhenny, 1941). The second nest cavity was excavated “a little lower than the nest of the year previous.” These are the only published records from Louisiana of Ivory-bills nesting in cypresses, and in fact the only nesting records for the species in the southern part of the state. In Florida, however, most Ivory-bill nests for which the tree species was recorded were in cypresses (Tanner, 1942). It is worth noting that most of these cypress nests in Florida were within 30 mi of the coast. Across the range, 80% of Ivory-bill nests within 30 mi of the coast were in cypresses. The only other published account of Ivory-bills renesting in the same tree is apparently that of Scott (1888), who found an Ivory-bill nest in a large cypress near Tarpon Springs, Florida, and stated that “The same cavity had apparently been used before for a nesting place.”

McIlhenny (in Bendire, 1895) mentioned Ivory-bills feeding on live oak acorns, even stating that the species “stores acorns in holes for its winter supply. I have seen them destroy the nests of the gray squirrels to obtain the acorns and nuts they had put by for the winter.” This appears to be the only published report of Ivory-bills storing acorns. Other nuts, fruits, and seeds are reported in the diet, including poison ivy seeds, magnolia seeds, cherries, grapes, persimmons, hackberries, tupelo fruits, and pecans (Tanner, 1942). Lammertink et al. (1997) found indications that the Ivory-bill’s Mexican relative, the Imperial Woodpecker, raided the granaries of Acorn Woodpeckers in Mexico.

One of the most striking features of the historical literature on Ivory-bills is the absence of reports of “double-knocks” aside from those of Arthur Allen and James Tanner. Tanner often heard Ivory-bills producing single- and double-knocks, and double-knocks are typical of other Campephilus species. Allen and Kellogg (1937) specifically remarked that they had never heard Ivory-bills sound a real “tattoo” like other woodpeckers, and Tanner (1942) stated that “I have never heard anything resembling a continued drum.” McIlhenny however (in Bendire, 1895), stated that “one bird will alight on a dry limb of some tree and rap on it with its bill so fast and loud that it sounds like the roll of a snare drum….It braces itself with the stiff feathers of its tail, and in striking a blow uses the body from the legs up to give force to it. The blow it delivers in this position is very hard, and sounds as if some one was striking on a tree with a hammer.” Thompson (1885) seems to be the only other observer who reported Ivory-bills producing drums similar to those of other North American woodpeckers, and was even more explicit: “With two or three light preliminary taps on a hard heart-pine splinter, he proceeded to beat the regular woodpecker drum-call – that long rolling rattle made familiar to us all by the common red-head (Melanerpes erthrocephalus) and our other smaller woodpeckers.” Allen’s Singer Tract recordings of Ivory-bills do contain some rapid tapping, probably displacement behavior due to the presence of the human observers. Such tapping may have been mistaken for drumming by McIlhenny and Thompson. Interestingly, Nelson (1898) reported that, regarding the Imperial Woodpecker, “Now and then one ‘drums’ for amusement upon a resonant branch or trunk after the manner of many smaller Woodpeckers, but the strokes are much louder and slower than those of the other species.”

McIlhenny (in Bendire, 1895) stated that, regarding Ivory-bills, “As soon as they leave the woods they mount to a considerable height, their flight being very strong, and, like that of all Woodpeckers, undulating.” Audubon (1831) described the long flights of Ivory-bills as featuring “deep undulations.” Tanner (1942) reported Ivory-bill flight as “strong and usually direct, with steady wing-beats.” He did observe one Ivory-bill flying a short distance with “an undulating, swooping flight.” North American woodpeckers, including Pileateds, typically fly in a mode known as flap-bounding, employing frequent folded-wing pauses (Tobalske, 2001). This yields an undulating flight path. Tanner’s observations suggest that this would be quite unusual for Ivory-bills. However, films of the closely-related Imperial Woodpecker (Lammertink et al., 2011) contain 3 short flight segments. All 3 show rapid, rather steady wingbeats, yet 2 of these segments also contain brief folded-wing pauses. Such flight could easily be interpreted as “strong and direct, with steady wing-beats,” yet also be interpreted as “undulating.”

In 1937 Tanner wrote to McIlhenny about Ivory-bills, who replied that “There are a few Ivory-bills in the swamp on the east side of Avery Island – three or four pairs, I think. They do not seem to increase, for about the same number have been here since I was a child. I saw one about two weeks ago on the hillsides, and it was apparently in search of a mate at that time, from its calls.” Tanner visited him later that year. In his journal7, he reported that McIlhenny again told him that he had seen an Ivory-bill earlier that same year (Fig. 13). McIlhenny also told Tanner that he had seen none the year before, and 2 the year before that, and that a head had been brought to him 2-3 years before from “B. Sale,” undoubtedly the Bayou Sale area of the coastal forest in St. Mary Parish, about 30 mi east of Avery Island.

Fig. 13. Excerpt from James Tanner’s journal, Jul 1937, describing his visit to Avery Island.

By the mid 1930’s, the vast majority of cypress logging in the Atchafalaya Basin and Louisiana coastal forest was decades in the past. Louisiana cypress production peaked in 1913 (Fig. 14). By 1931, cypress production had declined by 93% from its 1913 peak. Some of the largest cypress mills in southern Louisiana, including the F.B. Williams and Albert Hanson mills, both in St. Mary Parish, had cut their last cypresses by this time.

Fig. 14. Louisiana cypress production, 1904-1934 (Reynolds and Pierson, 1939).

In 1917, 86% of the cypress acreage in Louisiana was characterized as “denuded cypress.” McIlhenny’s statement that logging proceeded from east to west in the coastal forest is borne out by annual reports of the Louisiana Tax Commission, which document historical acreages of uncut cypress forest parish by parish. In 1918, only 3493 acres of uncut cypress remained in St. Mary Parish, while Iberia Parish contained 12,140 acres. By 1926, all of the cypress forest in St. Mary Parish was described as “denuded.” 2668 acres of uncut cypress forest remained in Iberia Parish at this time (Fig. 15). By 1933, all of the cypress forest in Iberia Parish was reported as “denuded.”

Fig. 15. Estimated acreages of uncut cypress forest in St. Mary and Iberia Parishes, 1918-1933. Source: Annual reports of the Louisiana Tax Commission.

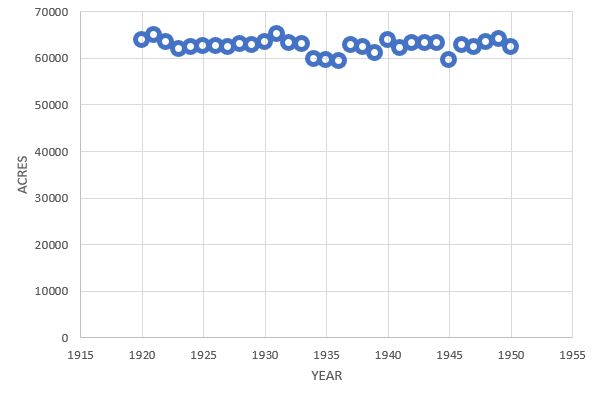

A 1932 forest inventory characterized 99% of the forest land in St. Mary Parish, 62,778 acres, as “cutover cypress” (Sonderegger, 1933). In Iberia Parish, 68% of the forest land was characterized as “cutover cypress,” with another 23% classified as “cutover hardwood.” Although timber operations continued in St. Mary Parish after 1930, total forest acreage remained essentially unchanged from 1920 to 1950 (Fig. 16). As noted above, Ivory-bills were apparently still being found in the coastal forest during the mid 1930’s.

FIG. 16. Total forest acreage estimated by the Louisiana Tax Commission in St. Mary Parish, 1920-1950.

In 1937, the same year Tanner visited Avery Island, the USGS published its Derouen quadrangle, which covered Avery Island and the adjacent Avery Swamp (Fig. 17). The swamp had been logged about 18 years prior. The distribution of forest (including scrub) roughly corresponds to that mapped in the 1911 soil survey as well as that reported by 19th century land surveyors.

Fig. 17. Portion of the 1937 USGS Derouen quadrangle, showing Avery Island and nearby forests. This quadrangle was published the same year that Tanner visited McIlhenny at Avery Island. Forested areas (including scrub) are shown in green. The black line is 1 mi in length. Source: USGS Historical Topographic Map Explorer.

In 1920, after the Avery Swamp logging in 1918-1919, a careful search of the area revealed only 3 of the birds, including a pair that nested (McIlhenny, 1941). The same pair nested in 1921 in the same tree. As noted above, this was the second time McIlhenny reported ivory-bills nesting twice in the same tree, something Tanner never observed. McIlhenny reported that a single bird was seen in 1923, and “none since.” He may have meant no nesting pairs, since this seems to directly contradict his statements to Tanner in 1937, both in writing and in person.

In any case, it seems likely that McIlhenny was being optimistic when he told Tanner that there were “three or four pairs, I think” of Ivory-bills in the Avery Swamp in 1937. It is fairly apparent from his 1941 paper that he found no indication of Ivory-bills nesting in the vicinity of Avery Island after the 1920’s. Nevertheless, it seems clear that at least 2 pairs of Ivory-bills nested in the forests on and near Avery Island in the 1890’s, and quite possibly as many as 5-7 pairs inhabited the area, although these higher numbers may not have been sustained annually.

Adding the area of the Avery Swamp to that of the Island, along with the bottomland hardwood forests, maple swamps, and willow swamps in the vicinity, gives a combined area of 16.54 mi2. However, as noted above, much of the so-called swamp was not forest, but scrub. Based on the 19th century surveys, this scrub area encompassed 4.96 mi2, reducing the actual forest area on and near Avery Island to 11.58 mi2. This implies 1.7-6.0 Ivory-bill pairs/10 mi2 of forest, or 1 pair/1.7-5.8 mi2.

Tanner clearly believed that the Singer Tract prior to logging was almost ideal habitat for Ivory-bills. He mentioned high rates of tree death in parts of the tract, and repeatedly emphasized the importance of dead and dying trees for forage, particularly at nesting time. He concluded that the Ivory-bill was likely a foraging specialist and had always been uncommon. Based on the reports of hunters, cowmen, and game wardens, Tanner estimated the density of Ivory-bills on the Singer Tract in 1934 at 7 pairs in 120 mi2, or 1 pair/17 mi2. However, Tanner noted that the Ivory-bills spent most of their time on the higher ground within the tract, which was a minority of the forest area. If we include only the areas circumscribed by him as those in which the birds “almost always ranged,” we get a much higher density of about 1 pair/6 mi2. Based on his analysis of Arthur T. Wayne’s field catalogue, he estimated the density of Ivory-bills in the Wacissa/Aucilla region of Florida prior to intensive collecting at about 1 pair/6 mi2. He considered this to be close to the maximum ivory-bill carrying capacity in “primitive areas,” and many of his estimates of local population densities at the time of his study were contingent on his assumptions about local carrying capacities.

Snyder et al. (2009) rejected Tanner’s carrying capacity estimates, citing numerous early accounts describing the bird’s abundance. Tanner himself acknowledged that in the Singer Tract “Those who have known this area for many years, such as the old hunters, cowmen, and wardens, claim that Ivory-bills were once quite common in the tract, more numerous than in recent years.” Snyder argued that the killing of individual Ivory-bills had a much greater impact on population densities than Tanner was willing to acknowledge. Tanner received second-hand reports of the shooting of Ivory-bills in the Singer Tract during the 1930’s, and was told by local residents in Florida that they had sold Ivory-bill parts as curiosities. Mason Spencer, who hunted in the Singer Tract, believed that shooting was a major cause of the decline of the species there. Shooting at the time was not restricted to collecting for museums and the like. Rural residents shot the birds for food, to adorn themselves with their parts, or simply out of curiosity, to get a close look at the animal. Such killing, mostly undocumented, may well have far exceeded the documented mortality resulting from specimen collecting.

Tanner placed great emphasis on sweet gum/oak forests as Ivory-bill habitat in Louisiana, stating that “The sweet gum-oak bottomland forest was and is the habitat of the Ivory-bill in the Mississippi Delta, and is also the forest association that supports the greatest number of other woodpeckers; both the cypress-tupelo swamp association and the overcup oak-water hickory association are forest types which Ivory-bills rarely inhabit and which support fewer numbers of all woodpeckers than does the sweet gum-oak association.” He dismissed even uncut overcup oak flats as “unsuitable” for the species, and cypress-gum swamp as “poor for Ivory-bills.” In fact, there is no evidence that sweet gum/oak forests support exceptionally high densities of woodpeckers generally, compared to other forest types. In Louisiana today, the greatest abundances of Pileated Woodpeckers occur in the southern Atchafalaya Basin (Fink et al., 2021). Beyer (1900) found Ivory-bills nesting in an overcup oak “in the midst of a heavy cypress swamp” only 8 mi from the Singer Tract, and collected no less than 7 Ivory-bills from this area. Tanner’s own review shows that 73% of Ivory-bill nests from Florida for which the nest tree was identified were in cypress trees, and 43% of all reported Ivory-bill nest trees were cypresses.

Although Tanner used the word territory in his study, there is zero evidence of genuine territoriality in the Ivory-bill. When a second pair of Ivory-bills met his John’s Bayou pair, he observed no agonistic behavior whatever, only indifference. Such a thing would be unheard of in a territorial woodpecker. Tanner himself stated, “Although Ivory-bills may appear to have nesting territories, like other birds, there is yet no evidence that they defend these territories from other Ivory-bills.”

Since it is quite possible that the Ivory-bill population in the Singer Tract had been significantly reduced by human predation by the time of Tanner’s study, and there is no evidence that pairs maintain exclusive access to nesting areas, the Tract may have been capable of supporting considerably more Ivory-bills than Tanner believed. On at least 2 occasions, the Singer Tract game warden J.J. Kuhn observed pairs of Ivory-bills in the Tract that succeeded in fledging 4 young at a time, in 1931 and again in 1936. Over a 9-year period, Tanner reported a total of 19 fledged Ivory-bills from 9 nests, and found that the mean number of fledglings from successful nests was only 1.4% less than that for Pileateds in the Tract. He reported no evidence that nest failures were due to forage limitations.

The John’s Bayou pair of Ivory-bills in the Singer Tract appears to have fed very heavily on larval wood-borers, and in particular used them to provision their young. Tanner emphasized bark-peeling as a foraging method for Ivory-bills, suggesting that they were further specialized for feeding on borers residing just under the bark. Tanner concluded that forage is necessarily quite limiting for Ivory-bills, with an individual pair requiring a minimum of 6 mi2 of forest in which to successfully nest.

Snyder et al. (2009) argued that the Ivory-bill was likely much less of a foraging specialist than Tanner concluded. Tanner recorded the “number of observations” of Ivory-bills peeling bark versus digging, and found that 72% of the observations were of bark-peeling. Unfortunately, he did not provide us with the actual times the birds spent in these activities, nor is there any way to know the relative volumes of deep versus superficial borers the birds were obtaining. Deep borers tend to be more abundant than superficial borers, as Tanner observed, and some species are quite gregarious. Tanner noted that Ivory-bills were extremely adept at deep excavation: “They dig with unbelievable rapidity in soft wood like hackberry, chiseling out a hole five inches deep in less than a minute. Their strength was again demonstrated when I saw one dig to the center of a live oak limb five inches in diameter and also into a living oak trunk.”

Ivory-bills do not regurgitate food to their young. Because of this they require heavy concentrations of readily-accessible food items that can be carried in their bills to the nest. Ivory-bills are well adapted for bark-peeling, enabling them to quickly expose large areas of the wood surface. However, it is not merely bark beetles and cambium borers that can be accessed by bark-peeling. Sapwood borers can also be exposed, and many deep borers can be found near the surface at certain stages. For example, the cerambycid Neoclytus acuminatus, which feeds on a variety of tree species, is a sapwood borer whose tunnels are often exposed by bark-peeling. Tanner (1942) reported fragments of the closely-related Neoclytus caprea from Ivory-bill nest debris. The deep-boring cerambycid Enaphalodes rufulus, which feeds on a variety of oaks, makes a cavelike opening under the bark during its first year. This borer is easily accessed by bark-peeling during this time. During its second year, it burrows deeply into the sapwood (Fig. 18), packing the cavelike entrance with frass. After removing the bark, a large woodpecker merely has to remove this frass and then extract the borer beneath with its tongue. The pupa of the deep boring, highly gregarious carpenterworm Prionoxystus robiniae, a generalist that feeds on a wide variety of trees, resides near the surface of the wood in the spring before metamorphosing into the adult moth. Individual moths of this species lay 200-1000 eggs, often in the same tree from which they emerge (Solomon, 1995).

Fig. 18. Gallery of the cerambycid Enaphalodes rufulus, showing cavelike portion under the bark and the deeper portion created during the second year. Image source: Fred Stephen, University of Arkansas, Bugwood.org.

The nesting densities reported by McIlhenny for the Avery Island/Avery Swamp area (1 pair/1.7-5.8 mi2) are 1-3.5 times those seen by Tanner at the Singer Tract, and 3-10 times those seen by Tanner if we include the entire Singer Tract (although less than a tenth of Tanner’s estimated density of Pileated Woodpeckers in the Singer Tract – 1 pair/0.17 mi2). Such Ivory-bill densities are wildly inconsistent with Tanner’s conclusions about the suitabilities and carrying capacities of potential Ivory-bill habitats. It is inconceivable that a large woodpecker highly specialized to feed on wood-borers in bottomland hardwood forests would have been able to nest at the densities indicated by McIlhenny in the forests on and near Avery Island. Tanner estimated that a single pair of Ivory-bills required a minimum of 6 mi2 of forest in which to nest. The combined area of hardwood-dominated forest on and near Avery Island in McIlhenny’s time was less than 5 mi2, sizable portions of it well detached from the Island and the Avery Swamp. More than half of the forest in the area consisted of cypress/tupelo swamp.

Although Ivory-bills may not be as specialized as Tanner believed, it stands to reason that heavy concentrations of wood-borers would increase their chances of successfully fledging young. The Wacissa/Aucilla region of Florida, where Wayne (1895) described Ivory-bills as “once very common,” but rapidly disappearing due to human predation, is only 10-20 mi from the coast. In 1877 it was impacted by a category 3 hurricane which produced a 12-foot storm surge at St. Marks, Florida. In 1886 this area was struck by not 1 but 2 category 2 hurricanes. In 1894 it was again affected by a category 3 hurricane. Disturbance events in the coastal forest have the potential to create abundant dead wood and/or stressed trees. A category 3 hurricane struck southwestern Louisiana in 1886, 6 years before McIlhenny found at least 2 Ivory-bill nests in the Avery Swamp. A category 1 hurricane scraped along the coast in 1897. The Great Galveston Hurricane of 1900 (category 4) produced hurricane-force winds along the coast of Louisiana and a significant storm surge. Another category 3 hurricane struck southwestern Louisiana in 1918, and a category 2 hurricane struck the south-central Louisiana coast in 1934. Frequent hurricanes would have no doubt yielded episodic increases in Ivory-bill forage, yet left large numbers of wind-resistant cypresses and water tupelos available for nesting. Although many coastal forest hardwoods resprout after hurricanes, they often do so well below the break, leaving a substantial portion of the bole to die (Fig. 19). Storm surges may induce significant hardwood mortality among species that are intolerant of even short-term salt water inundation. Prairie and/or marsh fires burning into the forests and scrublands during particularly dry years would have also enhanced tree mortality.

Fig. 19. Coastal forest water tupelo that has snapped, then resprouted well below the break point, leaving a substantial portion of the bole dead. The dead portion has extensive woodpecker excavations. St. Mary Parish, Louisiana.

Interestingly, McIlhenny (in Bendire 1895) stated that “When the young are hatched, both parents feed them, often going quite a distance into the open country in search of food.” One wonders what these birds were in pursuit of. Weeks Island, the only other sizable area of upland hardwood forest in the vicinity, is 4-6 mi from the forests of the Avery Swamp, and in any case Lockett (1871) stated that only about 600 acres (0.94 mi2) of Weeks Island was forested. This more or less agrees with the USGS mapping on the 1937 Derouen quadrangle. The nearest sizable tracts of forest to the north were near Jefferson Island, about 7 mi northwest, and near Lake Fausse Pointe, about 9 mi northeast. Round trips of 14-18 mi to provision young seem highly unlikely. Unattended nests would be vulnerable to predators. Tanner (1942) found that the John’s Bayou pair of Ivory-bills in the Singer Tract generally stayed within a 1.5-mile radius of their nest when incubating eggs or provisioning nestlings.

Small tracts of bottomland hardwood forest, totaling about 1 mi2, flanked Bayou Petite Anse about 2 mi north of Avery Island. Another tract of about 0.7 mi2 existed near the prairie/marsh ecotone about 2 mi north of the Avery Swamp. These forests contained live oak, red maple, sweet gum, and hackberry, all potential feeding trees, and have been included in the Ivory-bill density estimates above. Small patches of willow swamp, variously described as “willow marsh,” or “willow growth” by the surveyors, did exist in the area. I have mapped such tracts as were noted by the surveyors in Fig. 1, and these have also been included in the Ivory-bill density estimates. On the south boundary of Township 13 South, Range 4 East, surveyor John Boyd noted a “marsh grown up with willows” near the prairie/marsh ecotone. Such growth was no doubt widely scattered across the area, particularly along this ecotone. Black willow is a short-lived, wind-vulnerable species. Keeland and Gorham (2009) reported that about 15% of black willows in the southern Atchafalaya Basin were found to have died within 2 years of the passage of Hurricane Andrew. Willows are known to be the hosts of at least 5 lepidopteran wood-borers, 9 buprestids, and 5 cerambycids, including the hardwood stump borer Mallodon dasystomus and the carpenterworm Prionoxystus robiniae, both gregarious.

The southern portion of the Avery Swamp, and much of the eastern portion, consisted of wax myrtle/bay/live oak scrub, and remains so to this day. This is an unusual and apparently marginal environment for live oak despite its ubiquity in this area. The trees are generally quite stunted and a cursory examination revealed many dead individuals (Fig. 20). Live oak is known to host the buprestid Agrilus bilineatus, a sub-bark borer. Numerous other wood-borers are known to feed on oaks and it is likely that dead live oaks support some of them. It is quite possible that nesting Ivory-bills would find significant numbers of wood-borers in this scrub.

Fig. 20. Dead live oaks in the wax myrtle/bay/live oak scrub north of Weeks Island.

The other possibility is that the Ivory-bills in this area were supplementing wood-borer larvae with other prey items, as other congeners are known to do. Fragments of adult insects were identified in Ivory-bill nest debris collected by Tanner. We cannot conclude from Tanner’s observations that the Ivory-bill species as a whole is highly specialized on superficial wood-borers, even for provisioning young. Two Ivory-bill stomachs reported on by Beal (1911) averaged only 38.5% animal material. For many years it was widely believed that the Magellanic Woodpecker was specialized for feeding on wood-borers. Researchers in fact found that about 28% of the identifiable items used by nesting birds to provision their young were not wood-borers. Such items included spiders, caterpillars, adult insects, lizards, bird eggs, bird nestlings, and even bats (Ojeda and Chazzareta, 2006). In other cases in which woodpeckers were believed to be highly specialized, based on observational data or even fecal analysis, more detailed analysis has shown considerably less specialization. Gow et al. (2013) dissected Flicker fecal material from British Columbia and suggested that 99% of it consisted of ants. Yet Stillman et al. (2022) conducted DNA analyses of nestling Flicker fecal material from Washington and found that 4% of the 24 samples contained no detectable hymenopteran DNA at all. 63% of the samples contained some beetle DNA, 96% dipteran DNA, and 83% spider DNA, among others. The same study found that among nestling feces of the Black-backed Woodpecker, considered a wood-borer specialist based on observational studies, 6-7% of the 22 samples contained no coleopteran DNA. 39-79% of the samples contained some dipteran DNA, 36-39% spider DNA, and 36-44% lepidopteran DNA. The Black-backed Woodpecker research is particularly noteworthy, since this species has been considered, like the Ivory-bill, to focus on ephemeral patches of high-density forage, particularly wood-borer outbreaks.

In Tanner’s journal entry regarding his visit to McIlhenny in July of 1937, he stated that he was told by McIlhenny that Ivory-bills still inhabited the swamp averaging 4 miles in width running east from Avery Island to Morgan City, and that they “probably move around.” Tanner spent a few hours in the Avery Swamp just east of the Island, finding it to be “primarily tupelo and water gum, with water oak and cypress in some places.” Tanner considered the area unsuitable for Ivory-bills, despite the fact that McIlhenny had reported seeing an Ivory-bill in the area that very spring, and 2 of the birds a few years before. Tanner conducted cursory examinations of the coastal forest that year but appears to have spent little time in the forests themselves.

It is clear from the above survey data that the Avery Swamp always contained sizable amounts of tupelo (Nyssa spp.). However, it is also clear that most the larger trees in the swamp prior to logging were cypresses. Although Ivory-bills may forage on smaller trees, they require large trees to roost and nest in. Ivory-bill nesting season corresponds roughly to severe thunderstorm season in Louisiana, and the Ivory-bill has a long nestling period (about 5 weeks). Nest trees are prone to snap off at the cavities. The 6 Ivory-bill nest trees for which measurements were given (2 in Florida, 4 in Louisiana) were 13-19 in diameter at the nest (Hoyt, 1905; Tanner, 1942). These nests were 40-70 ft above the ground. In the coastal forest, few species of trees can achieve large diameters at such heights, due to frequent hurricanes. Cypress, however, is extremely wind-resistant and individual trees survive many hurricanes. Keeland and Gorham (2009) found that less than 2% of cypresses in the southern Atchafalaya Basin had died within 2 years after the passage of Hurricane Andrew.

As mentioned above, the Ivory-bill has a long nestling period, even longer than that of the Pileated Woodpecker, which is known to suffer heavy nest predation from rat snakes in Arkansas. Nest success probability in this species was found to be higher in cypress/tupelo swamps than in nearby bottomland hardwood forests (Noel and Bednarz, 2009). Newell (2008), in a study of Pileated Woodpeckers in bottomland hardwood forests in southern Concordia Parish, found that 46% of nest cavities were in “decadent” trees. Only 17% were in “vigorous” trees, and only 8% were in dead trees. During her study, 3 cavity trees broke off at the nest the same year that the nest was active. Almost a third of the nest trees were cypresses, despite the fact that the study was conducted in hardwood-dominated forest. Large trees were preferred for nesting; trees 80+ cm (31+ in) DBH were selected for nesting far out of proportion to their availability.

Tanner greatly emphasized available forage in Ivory-bill ecology, and seems to have given little consideration to the potential importance of nest site availability. Large trees that strike a delicate balance between structural integrity and predator defense may be quite limiting for Ivory-bills. McIlhenny stated that, regarding Ivory-bills, “I have never found a nest in wood in which there was sap, or in rotten wood” (in Bendire, 1895). In his journal, Tanner mentioned McIlhenny’s belief that cypress logging deprived Ivory-bills of potential nesting sites. McIlhenny observed a pair of Ivory-bills nesting in the same “deadened cypress” in consecutive years after the Avery Swamp was logged. Rat snake predation does not seem to have occurred to Tanner, who described the disappearance of Ivory-bill young from 3 nests as “really a mystery.” It is more difficult for a rat snake, or any potential predator, to conceal itself on a dead tree, or the dead portion of a living tree, than on a healthy, living tree. Snags tend to be isolated from adjacent trees, eliminating opportunities for snakes to cross over. Hoyt (1905), Phelps (1914), and Tanner (1942) all remarked that large amounts of bark seemed to have been removed from Ivory-bill nest trees, particularly near the nests. It is harder for a rat snake to climb a de-barked tree, and easier for a bird to knock it from the tree.

In 1909, J.P. and W.Y. Kemper conducted timber surveys in 3 sections in the southern part of Township 14 South, Range 14 East, and 10 sections in the adjacent northern part of Township 15 South, Range 14 east. This area is just southeast of Lake Verrett in the southern Atchafalaya Basin8. The lands had been acquired by the Williams Cypress Company over the previous 10 years and were eventually logged between 1920 and 1928. In other tracts in the region, these surveyors noted evidence of previous logging and deadening. In this area, however, they reported none. These timber surveys reveal much about the characteristics of cypress/tupelo swamps in this area prior to industrial logging (Table 2).

| surveyed section | area surveyed (acres) | mean tree volume/acre (board-feet) | % cypress by volume | mean volume/DC (board-feet) | mean volume DC/acre (board-feet) | mean number of DC/mi2 |

| 52 | 634.73 | 14,681 | 78.3% | 745 | 372 | 320 |

| 54 | 559.02 | 12,313 | 83.4% | 723 | 486 | 430 |

| 55 | 670.84 | 12,292 | 84.6% | 593 | 188 | 203 |

| 1 | 583.32 | 12,343 | 81.5% | 672 | 214 | 204 |

| 2 | 86.55 | 20,397 | 87.7% | 624 | 351 | 360 |

| 3 | 574.49 | 19,345 | 87.7% | 484 | 430 | 569 |

| 4 | 145.04 | 28,101 | 84.6% | 608 | 457 | 481 |

| 10 | 79.45 | 16,498 | 87.3% | 490 | 356 | 465 |

| 11 | 435.96 | 13,096 | 86.7% | 630 | 228 | 232 |

| 12 | 399.00 | 12,419 | 83.9% | 665 | 239 | 230 |

| 13 | 322.60 | 21,494 | 85.1% | 760 | 353 | 297 |

| 14 | 635.00 | 26,554 | 83.2% | 120 | 433 | 2309 |

| 15 | 158.28 | 27,899 | 82.3% | 536 | 463 | 553 |

TOTAL ACREAGE 5284.28

Table 2. Characteristics of cypress/tupelo forests in 13 sections southeast of Lake Verrett, Assumption Parish. Sections 52, 54, and 55 are in Township 14 South, Range 14 East. The remainder are in Township 15 South, Range 14 East. Surveyed by J.P. and W.Y. Kemper, 1909. DC – dead cypress.

In these sections, living cypresses averaged 3-5 times the volume per tree of “tupelo gum and ash,” again demonstrating that most of the larger trees in these coastal swamp forests were cypresses. Dead cypresses in these sections averaged about 588 board-ft/tree. Using the Doyle rule, this would correspond to a tree 28-30 inches in diameter yielding 2 16-foot logs, or 36-38 inches in diameter yielding a single 16-foot log. In “old-growth uncut” forests in the northeastern Louisiana delta region, Winters et al. (1938) found that trees in the 20-28 inch diameter range averaged 287 board-ft/tree, while those in the 30-38 inch diameter range averaged 609 board-ft/tree, and 40+ diameter trees averaged 1226 board-ft/tree. Therefore, 30-38 inches seems a reasonable estimate for the typical diameters of dead cypresses in the above sections, although some were undoubtedly much larger. As can be seen from the table, densities of dead cypresses were typically in the range of 200-600/mi2. These early timber cruisers often included downed trees in their estimates of dead tree volume. However, even if we exclude half of the dead trees in the above estimates, this translates into 100-300 cypress snags/mi2. The above surveys were conducted in October of 1909, shortly after a category 3 hurricane struck southeastern Louisiana in September. However, the Kempers stated that most of the trees downed by the storm were merely “shells,” and that the “actual storm damage is not great.”

The timber surveys cited above suggest that a single square mile of historical cypress/tupelo swamp in southern Louisiana typically contained hundreds of large cypress snags. Large snags are the element most conspicuously lacking in the coastal forest today. Large cypress snags may be critical for Ivory-bill nesting in the coastal forest, where hardwoods are seldom able to achieve large diameters high above ground. With their large-diameter boles that often protrude above surrounding trees, cypress snags may be ideal from the standpoint of predator defense. Yet nesting in an older, rotten snag during the height of thunderstorm season carries great risk, not only for eggs or nestlings but adults as well. Since only a fraction of snags may have recently died in a given area at a given time, they may be quite limiting for Ivory-bills. Because cypress is so long-lived, it will take centuries for large cypress snag densities to reach the levels that occurred historically.

In 1946, only 3 years after his paper on changes in bird life over the previous 60 years was published, McIlhenny suffered a debilitating stroke. Two years after that, in 1948, one of Tanner’s former students, Arthur MacMurray, was told by both the Singer Tract game warden and at least 2 local residents that Ivory-bills were still flying in Madison Parish. Edward Avery McIlhenny died on 8 Aug 1949. The Louisiana black bear virtually disappeared from most of South Louisiana in the mid 20th century, so much so that bears were imported into Louisiana from Minnesota in the 1960’s (Lowery, 1975). However, the coastal forest, much of it largely untraveled and difficult to access, retained its native bear population, which today is quite vigorous. The Ivory-bill, even in the 19th century, was often referred to as shy and wary of humans, preferring seclusion (Bendire, 1895; Hasbrouck, 1891; Scott, 1888). The coastal forest may have provided that seclusion. Decades after Tanner visited McIlhenny, Fielding Lewis reported Ivory-billed woodpeckers in the coastal forest of St. Mary Parish (Lewis, 1988). In the decades since, reports of Ivory-bills in the coastal forest of Louisiana and elsewhere have continued to come in.

1Field notes and township plats from Louisiana historical surveys of the General Land Office can be found here: https://wwwslodms.doa.la.gov/

2The townships referred to here are: Township 12 South, Range 11 East; Township 12 South, Range 12 East; Township 13 South, Range 11 East; Township 13 South, Range 12 East. This area lies generally between Lake Fausse Pointe and Lake Verrett in the southern Atchafalaya Basin.

31937 Correspondence between McIlhenny and Tanner can be found at the Avery Island archives.

4This correspondence was found in the Edward A. McIlhenny Natural History Collection at Louisiana State University.

5This correspondence between McIlhenny and Bendire was found in the Charles Bendire papers at the Library of Congress.

6This correspondence between McIlhenny and Arthur Allen was found in the Arthur A. Allen Papers within the Division of Rare and Manuscript Collections at Cornell University.

7James Tanner’s journal resides in the Division of Rare and Manuscript Collections at Cornell University.

8The Kemper’s timber surveys and those of others are housed at the Williams, Inc. land office in Patterson, Louisiana.

Literature Cited

Allen, A. A., and P. P. Kellogg. 1937. Recent observations on the Ivory-billed Woodpecker. Auk 54: 164–184.

Audubon, J.J. 1831. Ornithological Biography, or an Account of the Habits of the Birds of the United States of America. 1:341-347.

Bales, S.L. 2010. Ghost Birds: Jim Tanner and the Quest for the Ivory-billed Woodpecker, 1935-1941. Univ. of Tennessee Press, Knoxville.

Beal, F.E.L. 1911. Food of the woodpeckers of the United States. Bull. U.S. Bur. Biol. Survey No. 37:62-63.

Bendire, C.E. 1895. Life Histories of North American Birds, Volume 2, From the Parrots to the Grackles: With Special Reference to their Breeding Habits and Eggs. United States National Museum Bulletin 3:42-45.

Bent, A.C. 1939. Life Histories of North American Woodpeckers. United States National Museum Bulletin 174:1-12. (Ivory-bill entry prepared by Arthur A. Allen)

Beyer, G.E. 1900. The Ivory-billed Woodpecker in Louisiana. Auk 17:97–99.

Dunn, H.H. 1921. A bear hunt in Louisiana. The Wide World 48:142-149.

Fink, D., T. Auer, A. Johnston, M. Strimas-Mackey, O. Robinson, S. Ligocki, W. Hochachka, L. Jaromczyk, C. Wood, I. Davies, M. Iliff, L. Seitz. 2021. eBird Status and Trends, Data Version: 2020. https://science.ebird.org/en/status-and-trends/species/pilwoo/abundance-map

Gow, E.A., K.L. Wiebe, and R.J. Higgins. 2013. Lack of diet segregation during breeding by male and female Northern Flickers foraging on ants. J. Field Ornithology 84:262–269.

Haney, J.C. 2021. Woody’s Last Laugh: How the “Extinct” Ivory-billed Woodpecker Fools Us into Making 53 Thinking Errors. Changemakers Books, Winchester, Washington.

Hasbrouck, E.M. 1891. The present status of the ivory-billed woodpecker. Auk 8:174-186.

Hoyt, R.D. 1905. Nesting of the Ivory-billed Woodpecker in Florida. Warbler (2nd ser.) 1:52–55.

Keeland, B.D., and L.E. Gorham. 2009. Delayed tree mortality in the Atchafalaya Basin of southern Louisiana following Hurricane Andrew Wetlands 29:101-111.

Lammertink, J.M., J.A. Rojas-Tome, F.M. Casillas-Orona and R.L. Otto. 1997. Status and Conservation of Old-Growth Forests and Endemic Birds in the Pine-Oak Zone of the Sierra Madre Occidental, Mexico. WWF Biodiversity Support Program Publ. 160.

Lammertink, M, T.W. Gallagher, K.V. Rosenberg, J.W. Fitzpatrick, E. Liner, J. Rojas-Tome, and P. Escalante. 2011. Film documentation of the probably extinct Imperial Woodpecker (Campephilus imperialis). Auk 128:671-677.

Lewis, F. 1988. Tales of a Louisiana Duck Hunter. Little Atakapas Publishers, Inc., Franklin, La.

Lockett, S.H. 1871. Second Annual Report of the Topographic Survey of Louisiana. Office of the Republican, New Orleans.

Lowery, G.H. 1974. The Mammals of Louisiana and its Adjacent Waters. LSU Press.

McIlhenny, E.A. 1935. The Alligator’s Life History. The Christopher Publishing House, Boston.

McIlhenny, E.A. 1941. The passing of the Ivory-billed Woodpecker. Auk 58:582-584.

McIlhenny, E.A. 1943. Major changes in the bird life of southern Louisiana during sixty years. Auk 60:541-549.

Mann, C.J., and L.A. Kolbe. 1911. Soil Survey of Iberia Parish, Louisiana. U.S. Dept. of Agriculture, Government Printing Office.

Morgan, R. 1921. Bear hunting in a motor boat. Motor Boat 18:16-36.

Nelson, E.W. 1898. The Imperial Ivory-billed Woodpecker, Campephilus imperialis (Gould). Auk 15:217-223.

Newell, P.J. 2008. Pileated woodpeckers (Dryocopus pileatus) and saproxylic beetles in partial cut and uncut bottomland hardwood forests. M.S. Thesis, Louisiana State University.

Noel, B.L., and J.C. Bednarz. 2009. Breeding ecology of the Pileated Woodpecker (Dryocopus pileatus) in eastern Arkansas with reference to conservation of the Ivory-billed Woodpecker (Campephilus principalis): Progress in 2008. Unpublished report. Arkansas State University, Jonesboro, AR.

Ojeda, V.S., and M.L. Chazarreta. 2006. Provisioning of magellanic woodpecker (Campephilus magellanicus) nestlings with vertebrate prey. Wilson J. of Ornithology 118:251-254.

Ouchley, K. 2013. American Alligator: Ancient Predator in the Modern World. University Press of Florida, Gainesville.

Phelps, F.M. 1914. The resident bird life of the Big Cypress Swamp region. Wilson Bull. 26: 86–101.

Reynolds, R.V., and A.H. Pierson. 1939. Forest Products Statistics of the Southern States. U.S. Dept. of Agriculture Statistical Bull. No. 69.

Scott, W.E.D. 1888. Supplementary notes from the Gulf coast of Florida, with a description of a new species of Marsh Wren. Auk 5:185-186.

Snyder, N.F.R., D.E. Brown, and K.B. Clark. 2009. The Travails of Two Woodpeckers: Ivory-bills and Imperials. Univ. of New Mexico Press, Albuquerque.

Solomon, J.D. 1995. Guide to Insect Borers in North American Broadleaf Trees and Shrubs. U.S.D.A. Forest Service Agric. Handbook No. 706.

Sonderegger, V.H. 1933. Classification and Uses of Agricultural and Forest Lands in the State of Louisiana. La. Dept. of Conservation Bull. No. 24.

Stillman, A.N., M.V. Caiafa, T.J. Lorenz, M.A. Jusino, and M.W. Tingley. 2022. DNA metabarcoding reveals broad woodpecker diets in fire-maintained forests. Ornithology 139:1-14.

Tanner, J.T. 1942. The Ivory-Billed Woodpecker. National Audubon Society, N.Y.

Tanner, J.T. 1964. The decline and present status of the Imperial Woodpecker of Mexico. Auk 81:74-81.

Thompson, M. 1885. A red-headed family. The Elzevir Library 149:5-21.

Tobalske, B.W. 2001. Morphology, velocity, and intermittent flight in Birds. Am. Zool. 41:177-187.

Wayne, A.T. 1895. Notes on the birds of the Wacissa and Aucilla River Regions of Florida. Auk:362-367.

Winters, R.K., J.A. Putnam, and I.F. Eldredge. 1938. Forest Resources of the North-Louisiana Delta. U.S.D.A. Pub. No. 309.

Thanks for the work you put into this in depth paper

LikeLike